Gray matters

Though not glamorous, global population data is still a hot ticket in a library

As library purchases go, rare books and medieval manuscripts get most of the publicity, but most newly acquired materials lack the glitz and glamour that could earn them a turn in the spotlight.

Consider the recent purchase of a hefty hunk of global census publications. Paparazzi aren’t lining up at press events to take pictures of dense tables of data, yet these materials warranted a special purchase using the library’s Annual Fund for desiderata—expensive items desired by librarians but which fall outside the regular budget.

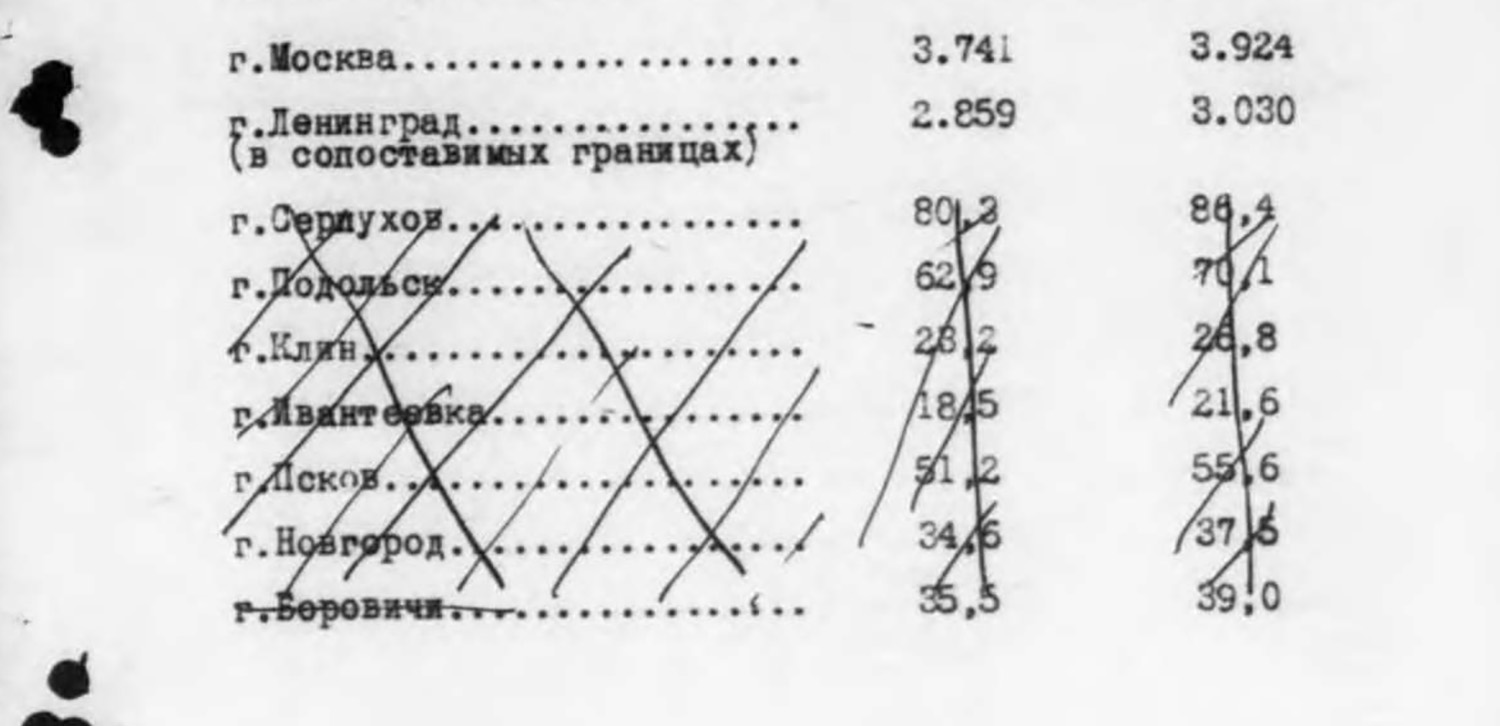

The archives include census publications dating back as far as the 19th century from Mexico, Colombia, Israel, Palestine, and Russia and the USSR. The materials, mostly scans of books, are filled with page after page of tables interrupted by the occasional map, bar graph, or litany of topographic details.

How did this gray expanse get marquee status on a librarians’ wish list?

“By themselves, census publications are the kind of resources that are difficult for a library to invest in, because how do you choose which countries? How do you choose which years?” said Anne Zald, a librarian who specializes in government documents.

But when a publisher bundles together so much data in a single package, it delivers a large collection of research products almost instantaneously.

Of course, a library can borrow a physical publication from another institution, but that has its own challenges. The borrowed item might come in a bulky set of tomes, or it might arrive on microfilm, a format that has “varying degrees of legibility,” Zald said. And waiting for an item to arrive can be a challenge in academic libraries, especially when the end of a quarter is a hard deadline for many.

Treasures amid the tables

Despite its dry appearance, a census document can provide torrents of valuable data for many disciplines and surprising insights into historic events.

For example, librarian Jeannette Moss was particularly intrigued to note that this purchase includes the 1939 census of the USSR, the earliest Soviet document in the archive. That census marks an infamous moment of propagandizing—and brutality—under Josef Stalin.

“Stalin believed that population growth was an indicator of economic success,” she said. Estimates in 1930 had suggested the population was around 160 million, so Stalin, assuming aggressive growth of a happy and productive citizenry, believed that the 1937 population should total 180 million.

But the 1937 count ended up well short at 162 million, even though it included penal colonies and remote villages. Compounding the propaganda trainwreck was a census question designed to determine how many people identified as religious.

“Some citizens were fearful this was a trap set by the atheist Communist government, and they denied having religious beliefs,” Moss said. Even accounting for this likely underrepresentation, the final census tally showed nearly 57 percent of Russians declaring a religious affiliation, another embarrassment for the Communist party.

Stalin was outraged. Many census workers were arrested and some were shot. Stalin suppressed the 1937 census results.

To no one’s surprise then, the 1939 census—easily reviewable in this archive—reflects a Soviet Union much closer to Stalin’s vision, including the 180 million number he had wanted all along. In a few tables, remnants of the 1937 data make an appearance, but the entire document is more a relic of Soviet policy than an accurate population count, Moss said. The Soviets did not conduct another survey for 20 years, after Stalin died.

Since then, international efforts have standardized the methods of tabulating accurate data, not just about population but about citizens’ occupations, travel distances to work, home ownership rates, and many other topics. Zald, who consults with Northwestern researchers who want to work with census data, is enthusiastic about the potential for government information to be relevant to nearly any discipline.

A 2018 history book on her desk, Census and Census Takers, contains a quote from an 1895 Brazilian census director, which she finds “charming.” In it the director calls the work “so noble that census agents should be considered apostles of civilization, of justice, and of the happiness of peoples.”

Zald hopes more members of the Northwestern community use this new archive to find that out for themselves.