Music Library exhibitions plumb old materials for new discoveries

New work invigorates the known history of medieval chant and Romantic classical music

The Music Library may be known for its concentration in 20th-century music, but head curator Greg MacAyeal knows some concertgoers just want to yell, “Play the old stuff!” This past academic year, the Libraries did just that, hosting two consequential projects that yielded discoveries in forms of music that predate the library’s most renowned holdings by centuries—in one instance, 12 of them.

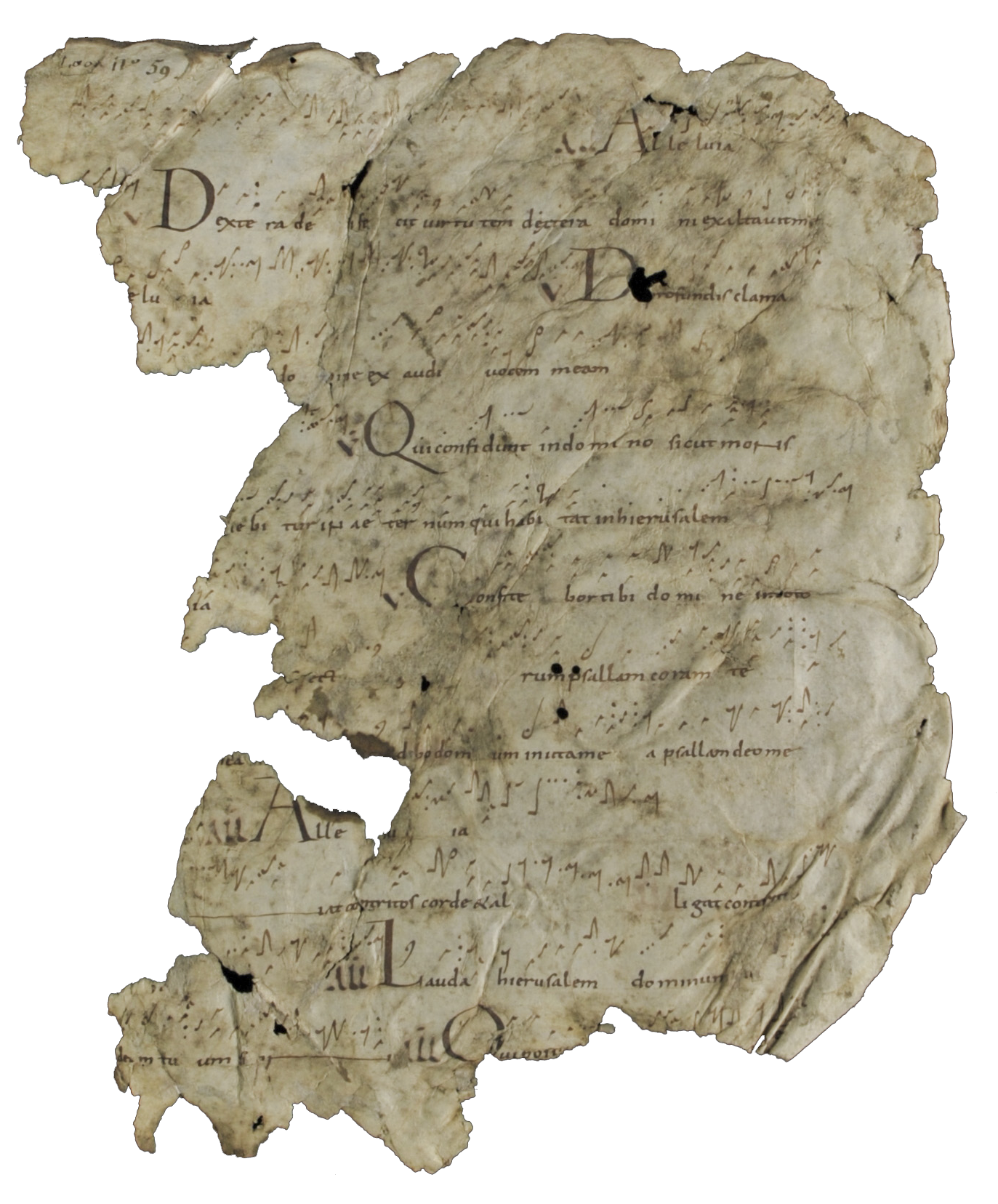

An exhibition of early music manuscripts led to the unearthing of a rare Gregorian plainchant document, and for more contemporary-minded listeners, an exhibition on Beethoven’s bassist brought sounds alive that haven’t been heard since the 18th century.

The Northwestern fragments

Last year, PhD candidates Paul Feller-Simmons and Phoenix Gonzalez led a group of fellow students to curate an exhibit on the earliest examples of written music found in the Music Library. Scripts and Performances: Uncharted Medieval Music Manuscripts at Northwestern University coincided with a national medieval studies conference held on campus in March.

The exhibit included church choir books dating to the 1200s, processional songbooks from the 1500s, and an array of uncataloged manuscript fragments showing the earliest forms of musical notation. Two such fragments caught the attention of international medievalists, who hailed them as “significant discoveries,” Feller-Simmons said. Such a dramatic find “is not usual in our field.”

One of the pages comes directly from the “most celebrated ninth-century book of Gregorian chant,” he said, called Graduel de Laon, or “Laon 239” as it is known in the field. Held by the municipal library of Laon, France, the unique document is one of the oldest music manuscripts with notation in existence, but it has been missing a page since at least the 1880s. That page appeared in the March exhibit.

MacAyeal is still researching how the fragment came to Northwestern, but as with many older acquisitions, the provenance is challenging to determine.

A second fragment contains a very early example of polyphony, or musical notation depicting more than one melodic line. (Earlier music was written for voices singing in unison.) That fragment is “distinctive for its unusually ornate style and its circulation in what appears to be an unofficial source” of church music, said Feller-Simmons.

Taken together, these unusual discoveries have gained Northwestern some notoriety among medieval musicology scholars, who quickly began to nickname the holdings “the Northwestern fragments,” MacAyeal said. Feller-Simmons is working with musicologists to identify more of the fragments, catalog them properly, and write a paper of the findings.

Beethoven’s bassist

MacAyeal worked with early-music historian and bassist Jerry Fuller ’75 to study a set of letters, legal papers, and musical notation belonging to Domenico Dragonetti, a Romantic-era musician most famous today as “Beethoven’s bassist.” The letters, part of the library’s extensive Moldenhauer Collection, led to an exploration of how Dragonetti viewed his craft and his legacy. As part of the online exhibit Digital Dragonetti, Fuller enlisted other musicians, several of them on the Northwestern faculty, to perform some of Dragonetti’s arrangements. To authentically recreate the sound of Dragonetti, Fuller had his bass converted to three strings to mimic the master’s configuration and playing style.

“What we’ve done is try, as best we can imagine, to recreate that sound world” of Dragonetti in 1836, Fuller said. “We can create that anew here with the information we found in the collection.”

In one exchange with Gioachino Rossini, the famous opera composer asked Dragonetti to “explain the advantages of both his bow and tuning method to help Rossini introduce Dragonetti’s methods into the curriculum of the Paris Conservatoire,” Fuller said.

Looking back at both exhibitions, MacAyeal is thrilled that the music collection can surprise people who thought they knew the library. “Everybody knows us for [20th-century composer] John Cage and for our strength in modern music,” he said. “Lesser known is the breadth of our collection. Exhibitions like these show we have real range.”